I awoke this morning thinking about Brian Coyle.

It’s been 26 years since he died, the first openly gay city council member in Minneapolis. I was the City Hall reporter for the Minneapolis Star Tribune, dumber than the day is long, but energetic, and curious and honest.

Unbeknownst to most of the world at the time, Brian had contracted HIV in the mid-80s and long before I got the City Hall Beat, he’d begun working covertly with a local magazine reporter on a story about this struggle with the virus.

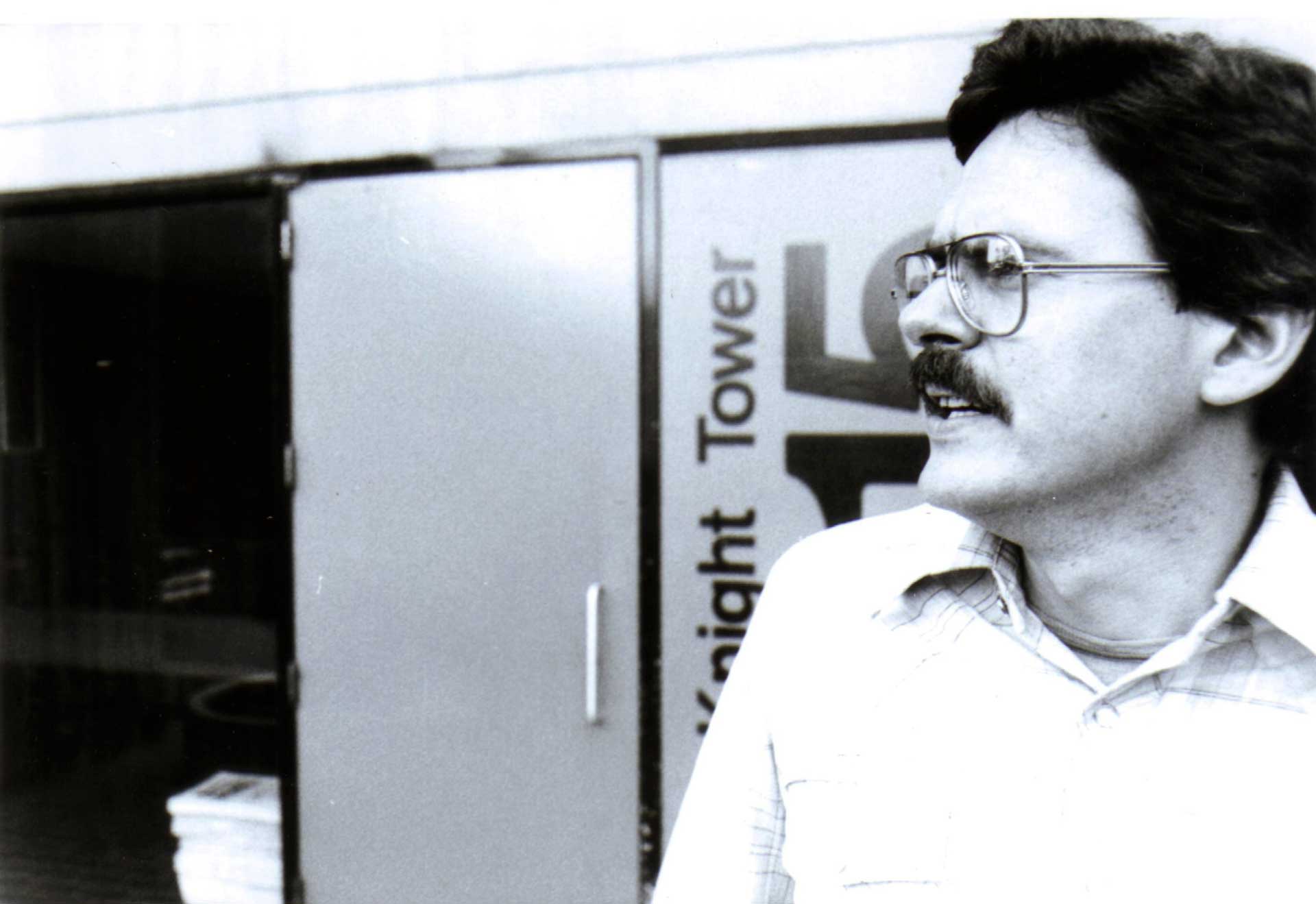

Brian was an intellectual, a conservative fat kid turned liberal gadfly, and remains to this day, perhaps the sharpest-dressed man I’ve ever personally known. He would invite me into his office and explain the city’s Fifth Ward to me, and the world, and when he laughed, it was an experience in itself, somewhere between a howl and a cackle, its sheer joy, and freedom reminding me of my father’s baritone laughter.

In the months leading up to his death, I suspected he was sick, not because he looked ill or had been unusually absent from work, but because his behavior became slightly more erratic; once, he berated me in front of his staff for a story I’d written which he believed reflected the kind of kneejerk liberalism that lost liberals elections. Both in tone and content, it was most un-Brian-like. I said nothing in response, and when he retreated back into his office, his secretary and I exchanged worried, knowing looks.

Days before the magazine story was to come out, rumors began to circulate that he was indeed ill, and he summoned me into his office one morning and shut the door behind me. The story was coming out because he knew he had not much longer to live, but he was concerned that it might make me–the Star Tribune’s young, black City Hall reporter–look bad if I got beat on the story revealing his illness.

So in one of the greatest acts of kindness and love ever shown me, he gave me the whole story, had me accompany him to the Red Door clinic, talk to his doctor, sit next to him while he took breathing treatments to keep pneumonia at bay. “This” he said to me after one exhalation from the plastic tube, “is the only thing I get to suck on these days, Jeter,” he said, and laughed that demonic, gorgeous laugh of his, so loud and defiant and full of the Blues that I couldn’t help but join him, laughing like an idiot as if the tube contained laughing gas that had cast a spell on the entire room. The doctor opened the door, shot us a damning look, then smiled and left.

My story on Brian’s illness was actually published BEFORE the magazine article by a day or two, and because Brian had given me so much information and access, it was arguably just as good. When he died a few months later, his sister called and left a message on my answering machine, saying that Brian had left her strict instructions to include me on the list of phone calls to be made.

I often think of Brian, but he’s been on my mind a lot in recent days. I heard a laugh that reminded me of his the other day, and it’s left me thinking about what it means to give a damn about another human being, and how, ultimately, that’s the only thing that will get us through.