This article first published 6/23/21 by the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder https://spokesman-recorder.com/2021/06/23/critical-race-theory-backlash-would-keep-the-truth-hidden/

When she taught at a prestigious Detroit prep school, Whitney Larkin would devote the first three weeks of her U.S. history course to an exploration of the Indigenous societies that preceded the arrival of the first European settlers. The textbook used by the class before Larkin began teaching the course glossed over this material in half a page, and the African American teacher thought it important that students learn about the pyramids of the ancient cities of Teotihuacan and the Cahokia, in addition to the Boston Tea Party.

“I want students to be clear that Indigenous peoples had highly complex societies that in many ways were superior to European ones. I go into great detail to emphasize this was not a barren, unpopulated land of hunter savages,” explained Larkin.

She said that while she was teaching the U.S. Constitution, a White student from an upper middle-class family responded to a question thusly: “The Constitution was written by old rich White men for old rich White men to keep them in power.”

Larkin responded, “I said, ‘Mic drop! My job here is done!’”

Some of the students’ parents, on the other hand, were not so keen about what their children were learning, and a coterie requested a meeting with Larkin and the dean of students. Larkin remembers meeting with three couples, although only the men spoke. When, they all asked, was she planning to teach “real” history?

“When I responded about White men’s history,” said Larkin, “they were shocked into silence.”

She was fired six months later.

Larkin’s experience four years ago shines a light on recent efforts to ban the teaching of critical race theory (CRT) in schools. Created by legal scholars in the 1980s, critical race theory posits that only institutionalized racism can explain the persistence of profound racial disparities in the workplace, education, political representation, household wealth and health outcomes nearly two generation’s after the Civil Rights Movement. As of this month, 25 states—including two Minnesota border states, Iowa and Wisconsin—have introduced legislation to regulate how teachers can discuss racism and sexism in the classroom.

But as Larkin and other educators point out, critical race theory is really just a proxy battle in a much larger war over dueling narratives, one that accounts for the suffering of People of Color, women, and the poor, and another that absolves those who are responsible for that suffering.

“I certainly teach critical race theory,” Ariela Gross, a law professor at the University of Southern California told the MSR. “I want our students to have active debate. I don’t really see racism as individual prejudice. Individualizing it, we can let ourselves off the hook.”

As have many others, Gross noted that few, if any, elementary or high schools teach critical race theory, nor is it widely taught at U.S. colleges and universities. “That’s telling,” said Gross.

She compared the backlash against critical race theory to efforts by White politicians in the 1960s to rally the troops, as it were, to crush any challenge to their privileges in the workplace, education and banking. She refers to proposals to crack down on critical race theory as “education suppression” that is motivated by the same White insecurities as voter suppression efforts that are gaining momentum in the post-Trump era.

“Most of the people who are passing these laws have no idea what CRT actually is. We often talk about ‘waving the bloody shirt’ when White southerners wanted to get White people riled up and appeal to their racism and remind them of the Civil War.”

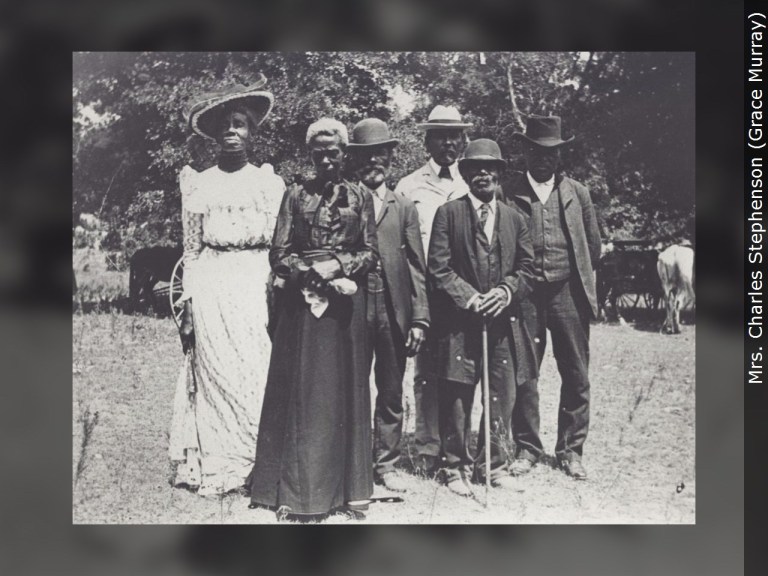

Whites, by-and-large, have always feared both the leveling effects of education and any vehicle by which the European settler project might be exposed for what it is: a racist colonization effort. Between 1865 and the mid-1870s, vigilante mobs set fire to scores of Freedmen’s schools, which were the precursor to universal public education. And many school districts across the South continue to refer to the Civil War as the “war of Northern aggression.”

Alternately, African Americans’ enthusiasm for “book learnin’” is the cornerstone of every Black social movement dating back to slavery. One administrator for the Freedmen’s Bureau—the federal agency responsible for managing the Reconstruction effort—compared Blacks’ support for public schools to a type of derangement, so “crazed” were they to learn.

A newly freed slave in Mississippi proclaimed, “If I nebber does nothing more while I live, I shall give my children a chance to go to school, for I considers education [the] next best ting to liberty.”

The tension between searching for truth and obscuring it is at the root of the debate over critical race theory. “This fight [over critical race theory] is more about the imagined feelings of White children learning the facts of history,” said Gross “There should be nothing taught that makes White children feel like they are racist or White Supremacists. It’s ironic because it’s being pushed by people on the side of the political spectrum who complain that their free speech is being limited.”

The timing is particularly troubling. The combination of the first African American president, Barack Obama, and a Great Recession that worsened the gap between the 99% and the wealthiest one percent, has deepened White anxiety, resulting in violence such as the January 6 attack on Capitol Hill. A broader public debate could help curb those violent impulses.

“It’s really dangerous when we start to shut down that history,” explained Gross.